From the Archives – An Interview With Harry Knight

The following is a short chapter from a book by Thomas Girtin, in the 1950’s Girtin interviewed various clothing makers for his book ‘Makers of Distinction’ including one Harry Knight from Cordings. Mr Knight relays stories of working his way from being a fifteen year old apprentice to manager. Along the way he had the privilege of dressing the royal household for the kings country pursuits as well as being the ‘go to’ in London for waterproof outwear.

We have recorded the interview in full – not only is it a first hand account of a pivotal moment in Cordings history, as the company navigated the changing mood in post war Britain, but also a snapshot of the wider changes happening in clothing manufacturing. Knight laments the loss of skills, the rise of mass production and more ominously the prevalence of ‘all that plastic’.

Nearly ninety years on, the story isn’t all doom and gloom. Cordings are still passionately supporting British and European mills and makers, some of whom have histories as long as Cordings and some of whom were already working with the company in the 1950’s. Slow fashion and sustainability are modern buzzwords for what we at Cordings have, since even before the days of Harry Knight always thought of as simply the right way to make clothing.

It Raineth Every Day

In England, above all countries, with its fascinating uncertainties of climate, it might well have been thought that craftsmanship would at any rate be safe among the ranks of the waterproofers. It was, after all, a Briton who gave the generic name by which raincoats of all materials tend to be known. Yet it is at this very point that the flame of individual craftsmanship suddenly flickers and dwindles to the very verge of extinction.

Certainly, this is a branch of the trade in which wholesale methods of manufacture were introduced at a very early date for waterproofs-‘bespoke’ it is true but mass-produced from block-patterns–were produced as early as 1899 and were soon purchased by customers who would never have dreamed of buying suits made under similar conditions. The portents that this holds for the future of craftsmanship are perhaps instructive.

The disadvantages inherent in Charles Macintosh’s patent in its early days had led to the invention by Thomas Burberry of the gabardine material which was to carry his name all over the world. And even though, within eight years of his moving to London from Basingstoke where the invention had first been made and marketed, the wholesale manufacture of Burberrys had begun, there was still sufficient individuality about the marketing to build up a formidable esprit de corps among satisfied customers, so that they talked of their ‘Old Burberrys’ as if they were valued human friends. They reported to the firm how these friends had stood by them in their hours of need which were many and varied.

Major Powell-Cotton, for example, ‘an experienced hunter of big-game (to quote from Open Spaces, the official history of the firm) was seized and shaken by a wounded lion while shooting in the Congo region. He was at the time wearing a suit of Burberry gabardine on which the infuriated animal’s claws certainly made some slight impression. Nevertheless, the Major was lucky enough to survive, as Livingstone did after a similar experience, and was not only able to testify to the wear and weatherproof qualities in his Burberry outfit but also to its service in minimising the injuries he would otherwise have sustained during his famous encounter.

Then, too, in Carbon Shooting in Newfoundland Mr Hesketh Pritchard, *the best lob-bowler of his day, advised his readers that ‘A good Burberry coat is a sine qua non.’

An eye-witness reported that as the Hampshire sank below the waves of the North Sea, Kitchener was seen to go down still wearing his old Burberry.

This loyalty was a splendid asset to the firm in the internecine strife which, from the earliest days, divided the waterproof trade into the two camps of those who wore Macintoshes and liked them and those who sought to prove that they were unhealthy. The latter even went so far as to compare, physiologically speaking, the wearing of rubberized clothing with the gilding of Sporus: that Roman boy’s untimely end through oxygen starvation of the skin awaited Macintosh wearers too and the cautionary tale was quoted with gloomy relish of a man who had dropped dead after a tramp across the moots in his rubber suit.

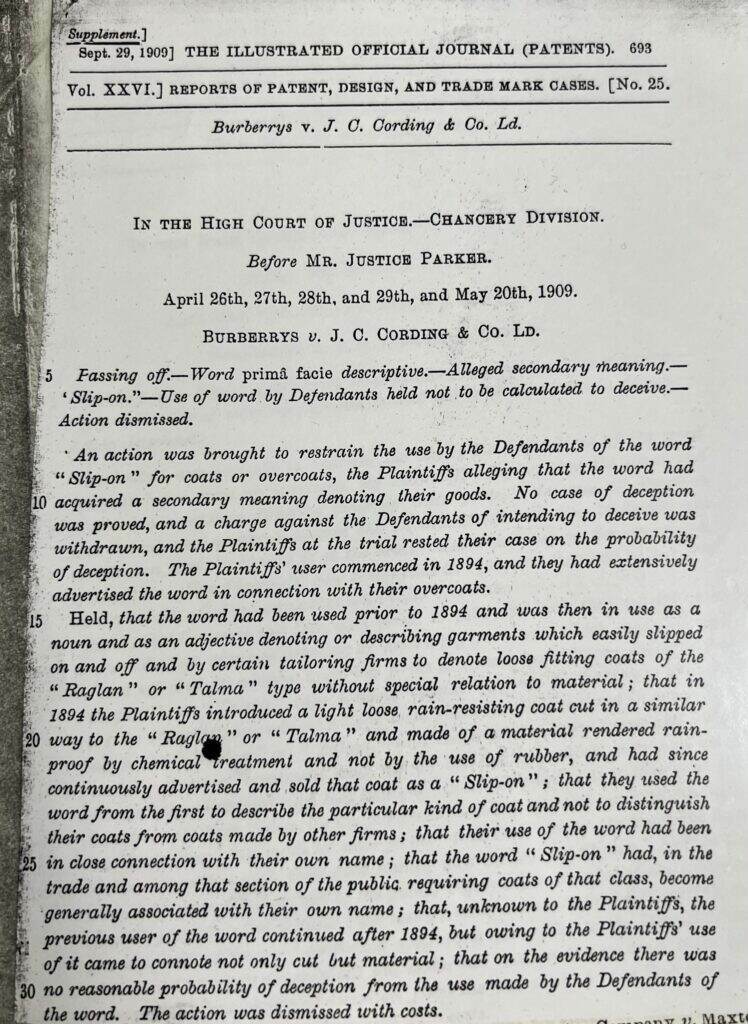

The contestants came into a head-on collision when Burberry’s sought to register the trademark ‘Slip-on’.

The proprietary rights in these words says Open Spaces, ‘were for over twenty years strictly respected by traders after they had been enlightened as to its sanctity by sundry Injunctions and other less incisive forms of legal admonition, but now that legal registration was involved a combination of trade competitors fought the case and after an action lasting a week were at last successful. So grateful were the smaller traders who had long smarted under legal admonitions’ that they presented the firm that had been responsible for organising the defence with, inter alia, a solid silver model of a pair of wrestlers.

This firm was Cording’s of Piccadilly whose shop window has long been noted by the cognoscenti for its unchanging old-world standards of display and for the boot which stands perpetually immersed in a tank of water; a trifle shabby from the incrustations of lime that evaporation has left, it has remained utterly waterproof for years on end.

Cording’s, the organisers and victors of the fray, are still very much the hand-made and made-to-order firm that they have always been. For every garment that they sell from out of stock three are specially ordered. For them the problems are basically those that beset other branches of the tailoring trade, although technically speaking, the tailoring of macintoshes calls for a greater amount of initial accuracy than that needed by the ordinary tailor. Cloth can be stretched or shrunk, it can be steamed or moulded. But rubberized material stays the way it is cut, so the cutting must be absolutely accurate the first time.

The ordinary tailor, moreover, makes his seams with an inlay that allows for a certain amount of adjustment in the initial stages of fitting. But the Macintosh maker has no such inlay. The material is stripped back at the edges with naphtha, doubled over, stitched, stuck with rubber solution and then taped with waterproof tape. This is one of the features distinguishing macintoshes of Cording’s standards from those of cheaper make, which are merely stitched and taped with the result that water may at length leak through.

Cording’s have other problems, too, that are common to other branches of the craft trades. Competition has been forced upon them, as it has been upon the shirt-makers, by those shops who stock ready-made water-proofs. In the old days, customers used to come up from the country to do all their shopping, perhaps for a whole year, in one fell swoop. As far as Cordings were concerned Wednesday was ‘country day’ on which people would come in and order as many as five or six waterproof garments at a time. Now there are many customers who demand Cording quality but who have no time to delay while the garment is made specially for them, even though this may take no longer than a week. They come flying in from New York and flying out again to Brussels or Paris and if they cannot take their Cordings ready-made–with them, then their custom is lost.

This hustle does not greatly impress the craftsman firms: Cordings themselves regard it as ‘Americanisation’ and they express themselves quite content to continue as they have always done, turning out sufficient waterproofs of quality to make an adequate living. But, all the same, business is business and for this reason, they are prepared for the convenience of hustling customers to stock a certain number of garments made by other firms and of other materials than Macintosh. The customer is, in fact, allowed to a certain extent to dictate. As with the tailors, fashions may be influenced by the individual or by the manufacturer himself.

Cording’s, for example, claim to have introduced both the short waterproof coat and the long sheepskin coat in which they made use of a material that had previously been confined to gloves and jerkins.

On such occasions, a prototype is made up and placed in the window to await the reactions of the public. A new fashion in waterproofs, once it has been adopted, has a life of about eighteen months before it is bastardised and, subsequently, indignantly rejected by the Cordings breed of customers.

These customers are, as everywhere else, changing.

Many of the old moneyed classes, Cordings reproachfully report, now think it smart, even if they have the means, to look shabby and plead poverty. This reproach is echoed in Pearl Binder’s observation that “the trouble today is that increasing numbers of gentlemen who ought to be dressed by Savile Row are becoming less interested in what they wear, so that soon it will only be South American millionaires who dress like English gentle-men.’

The South American millionaire, of course, feels as yet no compulsion to use shabbiness as a defence mechanism against class hatred: in the days before the Wars when English gentlemen also felt no need for such instinctive camouflage the Clubman, the Hunting Man or the Shooting Man each wore the clothes, including waterproofs, that were suitable for the occasion: on a wet Derby Day there was always a queue of men in grey top-hats in Cordings shop buying waterproofs. Now ‘any old raincoat will do’. Moreover, the plastic Macintosh is an unwelcome and unbecoming invader in the waterproof field and not all new types of customers appreciate the superior skills of the craft trades.

Many of them either have hot money that they wish to spend or they snobbishly want the cachet of a good label. Yet there are still those who appreciate value for money, hard-earned and carefully saved: one customer apparently down and out and, in fact, actually living at Rowton House, came to the shop in his rags to buy a pair of hand-made waterproof shoes. So satisfied was he with his purchase that, several years later when he had again saved sufficient from his pittance, he returned for a second pair.

But the days of the great patrons, even amongst those with untaxed income to dispose of, are altogether ended.

Gone are the days when, as with other tailors, two large families could support a modest business. Hunt servants, too, provided a regular source of income that has greatly decreased.

Old Mr Harry Knight, who has been with Cording’s for more than fifty years and who has hardly a grey hair in his head, recalls with nostalgia the days when he used to wait upon the Duke of Bedford at his house in Belgrave Square. The ducal establishment was a large one. In addition to the family and the servants, there were a number of broken-down old aristocrats who were allowed to gather at the house where they could be among members of their own class and take the horses out for exercise. His Grace used to order forty or fifty white-proofed coats at a time to say nothing of carriage aprons and loin cloths for the horses.

Then there was Colonel Barclay who one day summoned Mr Knight to go down to his office in the City.

And who do you want to see?’ said the commissionaire.

‘Well, you can’t see him.’

‘I can, y’know,’ said Mr Knight, pushing his way into the building with the true craftsman’s contempt for the non-mechanic.

‘But he’s in a Board Meeting.’

I don’t know about any Board Meeting: the Colonel told me to be here today at this time and here I am?

Of course, gentle little, steel-cored Mr Knight was very soon shewn into the Board Meeting.

“Ah, Knight! ” said the Colonel. ‘Glad to see you. Just go round, will you and measure all these gentlemen for fishing boots.’ And he then carried on with the ordinary business of the meeting while Mr Knight went around the great mahogany table and tapped each member of the Board in turn upon the shoulder and got him to stand up and have his measurements taken. Fifteen pairs of fishing boots was the order on that occasion.

Mr Knight came into the trade through no family connection. He entered the firm as a boy and learned the business as he went along without his employers quite realising what was happening. I had a strict master and I improved myself all the time,’ says Mr Knight. One day a vacancy occurred and Cordings realised that they had no need to advertise: the self-trained boy who had been through no official apprenticeship was told to take over a workshop which, after some modest demut, he did.

Fifty years later, with a gold hunter watch, suitably inscribed, in a wash-leather pouch, as witness to his loyalty and devotion to duty, he was still at work.

The old craftsmen, when he was a boy, were a rough lot, says Mr Knight. “They only worked so that they could get money for booze. As like as not you’d come into the workroom and find two of them, sitting on each end of a bench, dead to the world. And if you felt along under the bench there would be the old plugs of tobacco they’d stuck there. They were a dirty lot. Livestock and all that, too. And they might have a dirty bucket of water by the side of them and dip their sponges in that to damp a lovely clean length of grey cloth.’

But Mr Knight is now almost alone in his workshop.

For he is the last surviving cutter in the rubber-proofed garment department of Cordings.

“The last war didn’t help” explains Mr Knight with masterly understatement. ‘You couldn’t get the materials and then the workers were bombed out and left and now they aren’t coming into the trade. You can’t get the girls either. They say the job’s too smelly, too sticky with the rubber solution and that. I’ve always been perfectly happy in the job but there you are: you can’t get the workers. Yet every job you do is different and that makes it interesting. You get some special order and it’s something that nobody else except yourself can do.

‘This is a challenge that Mr Knight finds exhilarating. He can carry out any job that may be demanded. The gentleman rider who wanted for everyday wear a pair of macintosh breeches (I warned him he’d find them too hot but you couldn’t tell him?), the South African who ordered rubberised shirts and pyjamas for camping in the open in the veldt, jockeys demanding sweating suits–all these and many more have been unquestioningly accommodated by Mr Knight. ‘Anything that anybody wants, we can supply it,’ he boasts.

In this way, he is carrying on the early traditions of the craftsmen of the firm who could set their hand to anything, including a special order which emerged as “The Livingstone Pontoon Raft created for the great explorer pursuing his arduous career’ (as the Illustrated London News referred to it and which was destined to be the forerunner of the inflatable rubber dinghies used during World War I.

‘Yes! I’ve always been happy in my job,’ says Mr Knight and his unlined, unworried face bears witness to the fact. ‘And I wouldn’t change it. I’ve waited for them all. Royalties as well. Went to Buckingham Palace to wait on George V. Met him coming down the stairs. Soon fitted him up. The Duke of Connaught, too. Always asked me to sit down when I called. They were different, the aristocracy, in those days: they treated a man as if he was a human being.

The new lot, though different altogether those were who were created for their money.

Though it was Edward VII who made the West End, admits Mr Knight. ‘He would walk up St James’s Street with all the boys the betting lot-Lonsdale and all of them would go into Hook and Hole’s in Bond Street and meet all his friends in the back room there.’

‘That made Bond Street, that did. Made the West End.’

It’s never been the same since. The West End was busy all day long: even on the hottest days we’d be working away making waterproofs as long as Edward was in Town. We were busy then and we were quite glad to see him go off to Brighton or the Continent so that we could ease off a bit.

“And you had to work in those days seven o’clock at night on weekdays and five o’clock on Saturdays. The pay was nothing great either but I never wanted to change my job. Always something new. The Selby coats, for instance: cut like a cape with sleeves, they were, with great horn buttons on them. They cost £5 in those days and were all the thing for coaching. May Day was the great day for coaches and they used to sound off on their horns as they came up St James’s Street and then we’d be out on the pavement and hand their Selby coats up to them as they drove by. We supplied the barracks as well as the Palaces and the Royal Academy at Woolwich and then when motors came along we used to supply Rolls Royce with all their waterproof motoring clothes.”

That, as Mr Knight now realises, was the beginning of the end. For first the motors drove the coaches off the road and that was the end of the Selby coat. Then the motors became enclosed and that was the end of the waterproof clothes, for the riders of motor-bicycles were, on the whole, not to be considered as buyers in the same market. And with the new triumphs of technology, there came another and dreadful blow at the fortunes of the craft.

‘Just at the moment,’ says Mr Knight, “it’s all that plastic….”

First, the internal combustion engine, making possible a wholesale devastation and disruption in time of war, changing the whole tempo of the life of the moneyed classes in time of peace; then the man-made, mass-produced materials–these are the challenges to be faced not only by the waterproofers but by all the craft trades.

In some instances, the challenge has been met only by a total submerging of individuality. The offices of some of those with the old craft names and reputations in the waterproof industry now have an ambience very remote from that of the old craftsmen. The materials used are still, it is true, of that fine quality that is the hallmark of the English bespoke tailors and the workmanship, within the limits of mass production, is unexceptionable. But the atmosphere is very different from that in which the old craftsmen flourished. Connected conversation with the Managing Director for more than a few seconds at a time is barely possible: the telephone rings continuously, appointments are made for meetings in New York in two days time, in Edinburgh two days after that; bell-pushes are pressed, secretaries come, take notes, deliver files and go, advertising agents, folders in hand, wait expectantly. ‘If by craftsmen, says one of them breaking into mime, ‘you mean an old boy sitting cross-legged on a bench and stitching away with needle and thread–that’s out. Definitely.’

Is this the end to which the craft trades all must come?

Is this the inevitable outcome of the trend, already seen in Savile Row, towards a modified form of modern workshop practice? If so the future for the individualist craftsman must indeed be serious: mass-production makes no allowances for personal idiosyncrasies either in workman or customer. And, if this trend is confirmed, then the last traces of the superiority that drew the world to England for men’s requirements will disappear. Almost every country is capable of producing machine-made goods; yet comparatively few have been able to rival the English craftsmen. It is possible that this is a matter both of temperament and of atmosphere, for the English craftsman in the bespoke trades transported to other countries, seems seldom to have reproduced the qualities that were apparent in his native land.

If the individual craftsman is to become extinct then the market will become wide open to all competitors. The warning has been sounded; it now becomes necessary to pursue the craftsman into other spheres of the craft trades to consider further his chances of survival.